The Battle of Zama was an engagement in which the Romans under Scipio Africanus decisively defeated the Carthaginians led by Hannibal Barca, ending the Second Punic War. As the Romans marched on Carthage, Hannibal returned from Italy to defend the city. A combined force of Romans and Numidians under Masinissa overwhelmed Hannibal’s Carthaginian army. Carthage ceded Spain to Rome, gave up most of its ships, and began paying a 50-year indemnity to Rome.

The Second Punic War had been going on for a very long time. Hundreds of thousands of men had been lost on both sides. Nevertheless, Rome and Carthage continued the fight. Carthage, however, was on the decisively losing side of the conflict. The armies of the republic had pushed Carthaginian forces back on every front. Now Roman forces were at her very doorstep and were led by their commander, Publius Cornelius Scipio (236 – 183 BCE), who proved he was up for any challenge. However, not all was lost for the Carthaginians because Hannibal Barca, who was the greatest military mind, which Carthage had produced. For many historians, Hannibal was arguably one of the best military commanders in antiquity.

The Roman and Carthaginian armies met on a dry dusty plain in North Africa, which would one day be the country of Tunisia. These men were veteran commanders, who had never before been defeated in battle. Both generals had cunning minds, which placed them into a league of their own. Perhaps, this was the primary reason they decided to meet a few days before the battle. Scipio had managed to capture some of Hannibal spies in his camp, but instead of executing them, he gave these men a grand tour of his forces. He knew that they would report exactly what they saw. However, Scipio’s cavalry had not arrived yet, and he specifically wanted the spies to report that as well. But, Hannibal already knew about the missing cavalry, and his opponent’s use of deception intrigued him. He wanted to meet the man who he had heard so much about. This man employed similar battlefield tactics against Hannibal’s Carthaginian army. Likewise, Scipio too was fascinated with Hannibal. He was at the Battle of Cannae when he saw firsthand what Hannibal was capable of doing to a Roman army.

They met face to face the day before their armies were to fight. Scipio needed the time to bring in his cavalrymen and Hannibal wanted to arrange his new conscripts. However, it was more than just tactical maneuvering. They wanted to size each other up and perhaps they were just curious about what their opponent was really like. They quickly discovered that they had a lot in common. Hannibal was born into the upper class and was a consummate warrior. His father Hamilcar Barca, who was the military genius that defeated Roman armies in Sicily during the First Punic War, trained him. When it was Hannibal’s turn he decided to invade Italy in 218 BCE, and he won impressive confrontations at the Trebia River, Lake Trasimene, and Cannae, which historians still regarded as one of the most impressive triumphs in military history. His tactical maneuvers were like daggers thrusting deep into the hearts of the Romans, which almost brought their Republic to her knees.

However, the Romans decided to fight on. They adopted a policy of non-engagement to avoid a direct fight and instead played a battle of attrition that lasted for over a decade. The Carthaginian government was unable to provide timely reinforcements. Hannibal’s dutiful brothers Hasdrubal and Mago tried valiantly to come to his aid, but both men died in their attempt to help their sibling. They were significant casualties in this massive conflict. Nonetheless, Hannibal was not the only commander to lose his family members. Scipio was also born into aristocracy. He was the son of a Roman consul with the same name. His father and uncle were lost in the war. Carthaginian forces killed both men in Spain. Nevertheless, the young Scipio, who barely escaped death at the Battle of Cannae, would go on to command a Roman army. He took this force to Spain in the year 210 BCE, and then using military brilliance won decisively at New Carthage, Bakula, and Aleppo. This was his masterpiece of victory, and his baptism in fire. These deadly engagements honed Scipio’s abilities in tactical audacity.

It was in Spain when Scipio encountered the superb Numidian cavalry commander Masinissa (238 – 148 BCE), who at the time was working for the Carthaginians. Scipio knew he needed Masinissa’s expertise, and despite the fact this Numidian was partially responsible for the deaths of Scipio’s family members, the Roman commander went to work bringing Masinissa to the Roman side in 205 BCE. When Scipio returns to Rome, he became one of the youngest consuls in Roman history because of a unanimous vote. However, when he proposed the direct invasion of Carthage, the Roman leadership immediately rejected him after considerable effort. He was eventually able to get approval, but his political opponents denied him the ability to levy new forces in Rome. Scipio did manage to gain some volunteers in the capital, but he knew a place where he could find more men for the army. On the island of Sicily, the Roman leadership placed the 5th and 6th legions in exile. These were the remnants of the men, who had been defeated at the Battle of Cannae. They had been left there as punishment for their failure in combat. Scipio would give them an opportunity for their redemption when he incorporated these men into his army, and then retrained them to peak efficiency.

When his men were well prepared, the Roman commander invaded North Africa, and brushed aside a Carthaginian force at the Battle of the Great Plains in 203 BCE. This victory prompted the Carthaginian government to sue for peace, but in reality, they use the time to recall Hannibal from Italy. They would need him for a last ditch defense of the homeland. Hannibal answered the call and brought the remains of his army with him. These men were his veterans, and they also fought at the Battle of Cannae. Now they were fighting for the very continued existence of Carthage.

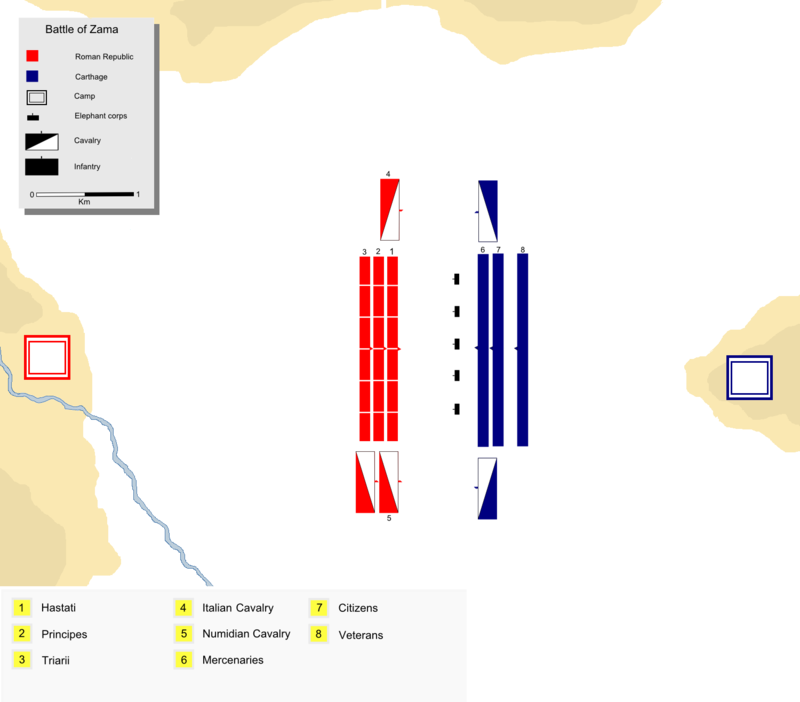

The Battle of Zama was really a rematch between men who were fighting on one side for their redemption and on the other side for their very survival. Hannibal was the first to arrive on the battlefield he had 36,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry, and 80 elephants. He deployed his infantry into three lines the first line consisted of his weakest mercenary troops. These were fighting men who he had very little time to train. His second line was citizen-soldiers. These people he levied from Carthage and Libya. His third and last line, he placed his veteran soldiers. These were his elite fighting men, who had served him well for more than 15 years. As Hannibal went into battle, he knew that Scipio was famous for his enveloping double pincer attack, which Scipio had done at the Battle of Ilipa, and thus he intentionally held back his third line to dissuade the Romans from doing this tactic. On both flanks, Hannibal placed his cavalry and with the intent of sending in an opening charging attack. He placed his elephants right in the front on the other end of the battlefield.

Scipio also had his forces in three lines. He had 29 thousand infantry and 6,000 cavalrymen. In typical Roman formation from front to back, were the Hastate, which were his youngest and least experienced followed by the Principes, who were men in the prime of their lives usually also rich enough to afford better equipment. Finally, the Triarii, who were the older but most experienced soldiers and best equipped of his forces. However, unlike typical roman formation, Scipio did not place his base units known as maniples in the standard checkerboard pattern, but rather in single file to create alleys between his men. This was done because he correctly guessed that Hannibal would bring his elephants to the field and this prepared his men for the attack on the flanks. He placed this numerically and militarily superior 6000 cavalry, which included on the right flank the Numidian prince and commander Masinissa, who felt it was now the Romans who gave him the best chance to claim his new Midian throne, which was kind of his goal all along. In the front of his line, Scipio placed his velities. These were skirmishers, who masked his true formation from Hannibal’s view. The battle began as Scipio had predicted. Hannibal charged out his elephants in a direct attack on the Roman center. As the elephants approached, Scipio ordered his cavalry to sound their horns, which frightened some of the animals causing some of them to run back into their own lines trampling those in the way especially on the Carthaginian left wing. As the rest of the elephants neared the Roman formation, the velities blended back into the line revealing the alleys between the soldiers. The elephants chose the path of least resistance running down the lanes, which made them easy targets when spearmen brought down the beasts by spearing the elephants on either side.

After Masinissa watched the Romans kill and injure Carthaginian elephants, he launched his cavalry into the Carthaginian left wing. The Roman cavalry on the other side under the command of Lylias did likewise. Unlike other battles where Hannibal had the superiority in cavalrymen and thus had the potential to unleash drastic and very mobile attacks at Zama, his cavalrymen were outnumbered and soon began to fall back. With no alternative, Hannibal ordered his cavalry commanders to withdraw, and lure their Roman and Numidian counterparts from the field, which worked. For all their tactical brilliance, the fight now between Hannibal and Scipio became an infantry brawl. Scipio sent in all three of his lines. Hannibal did the same, but he kept his veteran third line back in reserve just in case Scipio tried anything unusual. The Hastate smashed into Hannibal’s mercenary troops pushing them back, but Hannibal’s second line seeing a rout in the making began to lower their spears and they pointed them at their own comrades and thus got them back into the fight. The Carthaginian counter-attack drove into the Hastate, and destroyed their line. It was now the Romans turned to reinforce a crumbling front, which the Principes did. This counter and re-counter-attacks stopped both of Hannibal’s lines in their tracks. The fighting started to intensify and soon the Carthaginian line began to falter and break down. Seeing his enemies’ confusion, Scipio now gave the order to change the entire configuration of his army and extend his front line. His Hastates regrouped and formed the center. His Principes assembled on their flanks and the veteran Triarii rallied on the extreme wings. Perceiving the potential for an envelope meant Hannibal mirrored Scipio’s moves. He brought up his veteran soldiers to create a new center and then he assembled his mercenary and conscript Carthaginian and Libyan forces on the wings.

The Battle of Zama now came down to a single Roman line taking on a single Carthaginian one. This was a gruesome confrontation and at some point, Hannibal began to gain the upper hand when gaps began to form in Scipio’s forces. The Roman formation exhausted from fighting began to lose ground. However, when the battle appeared to be another major victory for Hannibal, the Roman and Numidian cavalry under Masinissa appeared again on the field, and the cavalrymen drove directly into the rear of Hannibal’s army and the results were inevitable because it was no longer a battle but a massacre.

The Carthaginians suffered 20,000 dead with another 20,000 captured. The Romans sustained fewer losses, but they had won the fight. The second Punic War was now over Carthage had to sue for peace and was strapped with a punishing treaty in massive indemnities. Scipio recognized Hannibal as being a worthy adversary and an honorable man. Their meeting before the battle only reinforced in the Roman commander that there was something redeeming in his opponent. Thus, rather than dragging Hannibal back to Rome in chains for a Roman triumphant celebration, Hannibal was allowed to live and would serve Carthage in an administrational role. Eventually, Hannibal would come to lead the establishment.

However, when the war ended, both men returned to governments that were hostile towards them. Hannibal did too good of a job in government. He brought wealth to the rank-and-file people instead of just the aristocracy. This incurred the wrath of other politicians who ironically reported him to the Romans and forced him to run for his own life. Hannibal became a fugitive when he went to the east, but eventually was cornered and decided to drink poison rather than ever becoming a Roman prisoner. For older Romans, Scipio had come too far too fast. Many of his colleagues in the Roman Senate hated him, and while they could not take down a war hero of his magnitude, they instead accused his brother of misdeeds. Eventually a disillusioned and frustrated Scipio would go into a voluntary exile. Strangely enough, both men died in the year 183 BCE. Hannibal died as he lived on his own terms as he drank the poison eyewitnesses remembered him saying, “let us relieve the Romans from the anxiety that they are so long experienced since they think it tries their patience too much to wait for an old man’s death.” Scipio made it a point for people to bury him away from the city of Rome. The inscription on his tombstone read “ungrateful country you shall not even possess my bones.”

Carthage recuperated from the war a little too well because she paid off her debts in no time and grew once again to be an economic powerhouse. This frightened the Romans who wanted her to be submissive at best. The Roman senator Cato the Elder became the biggest proponent for the annihilation of Carthage, and he would end all of his speeches saying, “Carthage must be destroyed.” Eventually, he got his wish about fifty years after the Second Punic War ended. The Third Punic War began with a Roman army under the command of Scipio’s adopted grandson. He was a man named Scipio Aemilianus (185 – 129 BCE), and he managed to take the city in 146 BCE. The pent up hatred that the Romans had for Carthage was finally unleashed. The Romans tore down Temples. They destroyed the city walls. They uprooted foundations. They dispersed the Carthaginian people and sold many of them into slavery. Scipio Aemilianus, then gave the final command to set whatever was left to the torch, and a firestorm of unprecedented magnitude consumed and gutted what was once the proud capital of an empire. However, when he watched the flames, he began to weep and he became pale at the sight.

Finally, while it is true that Hannibal Barca was a master tactician, Scipio Africanus appears to have been both a strategist and a tactician. Hannibal’s weakness was that his entire strategy was primarily battle centric. Hannibal is a good example of a commander who wins many battles, but he eventually loses the war because he knows no other strategy outside of military conflict. While it remains uncertain that the Carthaginians, because of their deficiency in resources, diplomacy, political leadership, and national determination, could have ever overpowered and occupied the Roman Empire, with a victory at Zama they could have remained a significant threat to prevent Rome’s future evolution into a major Mediterranean superpower. Instead, defeat ended the North African power and today almost nothing remains of Carthage.

PRIMARY SOURCES: Hans Delbruck (1990). Warfare in antiquity. University of Nebraska Press. Robert F. Pennel; Ancient Rome from the earliest times down to 476 A.D; 1890 Theodore Ayrault Dodge (2004-03-30). Hannibal: A History of the Art of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans Down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., with a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War. Da Capo Press. Polybius; The general history of Polybius, Volume 2; W. Baxter for J. Parker, 1823 Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart (1926). Scipio Africanus: Greater Than Napoleon. Greenhill Press. Paul K. Davis (2001-06-14). 100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 47. Flash Point History Vide