Taking place in December of 218 BCE, on or around the winter solstice, the Battle of the Trebia River was the first major battle of the Second Punic War between the Carthaginian troops of Hannibal and the Roman Republic. It was the first major battle of the war. With just around 10,000 of 40,000 Romans surviving and retiring to Placentia, it was a humiliating setback for the Romans, who suffered tremendous losses.

Following the defeat at Ticinus, the Roman senate attempts to salvage some dignity by blaming Gallic allies for their “ineffectiveness.” Longus’ arrival in northern Italy, despite the fact that Hannibal has not yet seen the legendary Roman soldiers, helps to restore confidence. As a result, Hannibal finds himself up against the troops of both Roman consuls. Because of the wounds he received at Ticinus, Publius Scipio’s life was still in danger in the early days of December 218 BCE. Ironically, however, his difficulties are only just getting started. His defeat at Ticinus has far-reaching ramifications for Rome, as it immediately led to the surrender of Clastidium’s huge grain storage, which was held by the garrison there. Consequently, his army loses access to its food supplies and its supply lines, making any push into enemy territory a high-risk undertaking in the first place.

As a result of this victory, Hannibal is able to refill his own stocks, which had been depleting ever since he descended from the Alps and had reached critical levels just a few days before the battle of Ticinus. The damage done to the Roman reputation increases the likelihood of more defections. What’s worse, Gallic tribes are flocking to Hannibal’s side, excited by his ability to defeat the Romans as well as his more tolerant approach to administrative matters. Scipio has no choice but to flee after recognizing that he has gotten himself into dangerous terrain. He marches to Placentia and establishes a camp on the other side of the Po River. Hannibal pursues and eventually catches up with them two days later. As soon as they learn of his arrival, approximately 2000 Gauls allied with Rome rise up in the camp and attack Roman soldiers, murdering many of them while they sleep. They cross the Trebia before daylight in order to join Hannibal, bearing with them the severed heads of Romans who had been murdered. Hannibal uses the Gallic defection as a propaganda tool, making sure to spread the notion that Rome’s friends are defecting in droves, so increasing his popularity among the tribal populations. Scipio marches south once again because he did not want the enemy to be able to catch up with him in the open. The next day he makes his way to the hills, where he establishes camp in a strategic location with hills guarding his sides from cavalry attacks.

After that, he settles in and awaits the arrival of reinforcements. By the middle of December, the two consuls have come together. During a discussion about how to attack Hannibal, Scipio argues against going the field, pointing out that Longus’ men lack experience and require extra training due to the fact that the Romans only recently raised them from the ashes. Longus, on the other hand, is not convinced and sets up camp a few kilometers north of Scipio’s position. While maintaining his camp on the flat plain and surveying the possible battleground west of the Trebia River, Hannibal, like Longus, is just as eager to fight as his opponent. He then dispatches a raiding party to attack the territory along the river, believing that the Gallic tribes who had previously pledged allegiance to him are now talking with the Romans, which he dispatched to ravage the land along the river. Even though it was unclear whether or not the Gauls planned to betray Hannibal, with their towns now being plundered, some of the tribesmen turn to the Romans for assistance. Longus responds by dispatching 1000 velites across the river to confront the invading hordes. With Hannibal’s forces dispersed over the region and burdened by loot, Roman troops begin to pick off small groups of Carthaginians, eventually routing the pirates. When the retreating raiding group is spotted, men on guard outside Hannibal’s camp rush to the help of the stranded soldiers. The fighting was intense because both sides were attempting to establish their superiority. The Carthaginians, on the other hand, were able to drive the Roman elites into a fighting retreat rather quickly.

It doesn’t take long for the skirmish to grow and extend throughout the entire neighborhood. As time goes on, more and more troops from both sides join in. As neither side was able to consolidate its forces, pockets of fighting began to occur. It becomes evident that the chaotic skirmish may escalate into a full-scale battle that neither commander will be able to manage. The situation becomes critical. Hannibal is the one who takes the initiative. He decides not to send any more troops into the combat, hoping to avoid being drawn into a battle that he had little to do with and had little influence over. He then rides out in person to rally the troops, which is considered bold at the time. His men are dragged away from the camp and lined up in a line outside the camp. However, Hannibal prevents his men from charging headlong into the Romans’ lines of battle. A similar stop was observed by the Romans who refused to assault the well-positioned Carthaginians because their army was being backed by missiles and new troops from a nearby Carthaginian camp. The day has come to an end. Hannibal exhibits his foresight by refusing to commit to a potentially bloody conflict. As an added bonus, he demonstrates what would later become his most well-known characteristic: his exceptional ability to exert authority over his army. The Romans return to their camp, delighted with their win against Hannibal’s forces and with their morale and confidence largely restored. Longus, who has been described as having an aggressive nature by sources, demonstrates his enthusiasm to engage in combat as soon as he can. He won’t have to hold his breath for long… The alarm is sounded by Roman guards at the crack of dawn. The Carthaginians have launched an attack on the camp! When the Roman commanders awaken to the sound of projectiles soaring over the palisades, they tell their troops to prepare for fight. The soldiers rush to form up in front of their tents in freezing temperatures, despite the fact that they have nothing to eat. Longus dispatches his entire cavalry force against the Numidians, who are closely pursued by 6000 velites. The Numidians, on the other hand, are quick to break away. As the combat progresses northward, the cavalrymen on the move engage in hit-and-run attacks. Longus marches out with the rest of his army to confront the enemy on the field of battle. Heavy infantry is organized into three columns, each of which is approximately 3.5 kilometers long. They are lagging behind the cavalry and the velites, but they are making good progress. The Numidians have maintained their efforts to avoid a direct confrontation with the Roman cavalry and velite infantry.

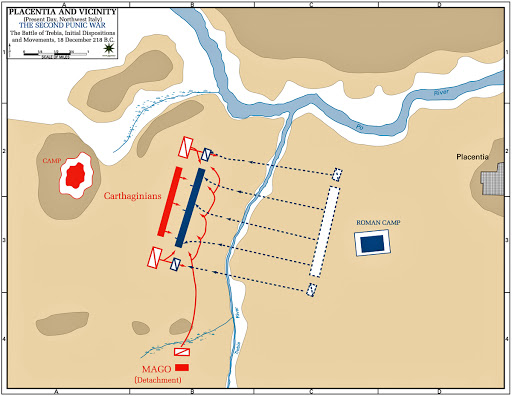

During this time, Hannibal collects his officers and lays forth his strategy. They are instructed to prepare the men for war after he has spoken words of encouragement. Carthaginian troops come to the field after a good night’s sleep and a good meal. The skirmishes are still going on to the east. The Numidians find themselves in a difficult position when facing the Trebia. They begin across the river as they continue to retreat from the Romans, who are closing in on them. Longus orders the army to deploy on the western bank of the river after arriving with the soldiers with a zeal for war. The three columns begin to cross the icy river, their chests buried in the frigid water. Meanwhile, Hannibal dispatches 8000 troops to the front lines to assist the Numidian retreat and to serve as a decoy for his own army’s deployment. He then advances his main line around 1km in the direction of the approaching Romans. Longus’ army takes several hours to get on the other side of the field. His men are famished and drenched after fording the frigid Trebia, and they are standing in temperatures that are approaching freezing. The Roman consul positions his velites in the foreground and his veteran soldiers in the center, flanked by Gallic and allied infantry on either side and cavalry on the sides of the formation. Using a thin line of soldiers, Hannibal positions his troops in the center, with Gallic allies on either side, and Spanish and Lybian men on either flank. Elephants guarded the infantry’s flanks, while the Numidian and Gallic cavalry advanced further to the right and left. Longus orders his entire line to attack about noon, confident in the overwhelming numerical advantage his heavy army has over the enemy. The Romans are marching forward in good order. The flat plain, which appears to be devoid of any impediments, appears to be an excellent battleground for their particular form of warfare.

Meanwhile, Hannibal maintains his position, allowing the enemy to close up on him. Combatants close the distance between them and begin trading projectiles. The Carthaginians immediately take the upper hand over the Roman velites, who had exhausted their javelin supply while pursuing the Numidian cavalry earlier in the day. With Balearic slingers in their ranks, combined with javelin eers, the Carthaginians quickly win the upper hand. During this time, skirmishers from both sides withdraw through the gaps as the main infantry lines close in around them. In the middle, Hannibal’s Gallic infantry suffers massive losses as the stronger, more compact Roman infantry pulls the Carthaginian line back. Hannibal orders his cavalry to advance on the flanks of the enemy army. Some of the Roman horses within the ranks are frightened by Hannibal’s elephants, which are generating confusion. While the cavalry fought the elephants, groups of Roman elites, who had been specially trained to cope with elephants, joined forces and attacked the terrible beasts, hurting and killing many of them. Numidians eventually manage to overcome and advance against the Roman cavalry. The Carthaginian center, on the other hand, was falling despite the fact that the Roman flanks were retreating. The Gallic infantry is being hacked to pieces by veteran legionnaires. Hannibal appears to be helpless in the face of the onslaught because he does not have any reinforcements. The Romans, on the other hand, are unaware that, while examining the battlefield on the eve of combat, Hannibal personally selected 2000 elite warriors and stationed them in a dry riverbed, out of sight. Suddenly, they appear from the ravine at precisely the right moment: just as the Numidians are about to rout the Roman cavalry, which is set to envelop the enemy. The Numidians attack the Roman army from behind, pressing them back with elephants, Carthaginian infantry, and skirmishers. The Roman infantry’s wings buckle under the pressure from the front.

As a result of their discipline and organization, the seasoned Roman heavy infantry cuts through through Hannibal’s center, causing the Carthaginian line to crumble. The legionaries, understanding that the battle had been lost, retreat back across the river to Placentia, where they retain their battle formation. Roman deaths are high, with estimates putting the figure at over 28,000 dead or wounded, whilst Carthaginian losses are significantly lower, with estimates putting the figure at between 3000 and 5000. Hannibal’s only significant setback at Trebia was the loss of the majority of his elephants. In a few of weeks, Hannibal had excelled both Roman consuls, thanks to greater preparation, near-perfect coordination, and complete command of his troops and forces. It is a shock to hear that Rome has been defeated, which results in widespread panic among the Roman populace. Many more Gauls are persuaded to join Hannibal as a result of the damage done to Roman prestige. Additional

PRIMARY SOURCES: Cottrell, Leonard (1992). “12. The Battle of Trebbia”. Hannibal: Enemy of Rome (reprint, illustrated ed.). Da Capo Press. Dodge, Theodore Ayrault (1891). “XIX. The Battle of the Trebia. December, 218 B.C.”. Hannibal. Gre